Melted wood?? Yes, melted wood. How else do you describe this hunk of mountain hemlock below? As the Covid-19 virus spreads around me here in Seattle, I have some extra time to also call the melted mountain hemlock below the subject for this week's Throwback Thursday. Today's post is short, so if you're curious about how a tree can become as mangled as this one, read on.

|

| From this view, we can appreciate some of Dan's deadwood carving, which starts to look more natural as it naturally weathers over time. |

Returning readers may guess correctly that this tree is one of the many beautiful yamadori (mountain/wild trees) collected and styled by Dan Robinson, on display at Elandan Gardens. This throwback is timely as I can use it to remind you, dear readers, that we are in the peak of the repotting season in Seattle right now! Next week I promise to have a more thorough repotting tutorial for all you beginners out there.

Below you see our subject before the repot operation. The pot has begun to fall apart or "delaminate" after years of exposure to cold (it may not have been a high-quality pot, as some clays fired at higher temperatures hold up fine for decades). Here you can prominently see that there is several inches of soil above the lip of the pot before we reach our trunk. In this repotting session, we worked to reduce that unnecessary height to fit the tree into a smaller pot.

|

| Before |

Below you can see several views of our finished tree in its new home! We began by working our way through the top layer of soil in search of major structural roots that could add to the nebari (the Japanese term for surface roots). In doing so, we managed to reveal an extra few inches of snakey trunk folded onto itself.

As you can imagine based on the fact that you don't see trees like this around your city block, this sort of structure to a tree is highly unusual. Most naturally formed bonsai trees (yamadori) are naturally stunted because they exist in an extreme environment. This tree came out of an intersection of two extreme environments - a highly acidic bog AND a mountainous area with heavy snow loading. Canada really is magical, if you can hack it through the government bureaucracy to bring live plants back over the border that is. The acidity of the soil does the work of slowing growth by inhibiting the uptake of Nitrate and other essential nutrients. The wetness does the work of limiting the space that roots can occupy to grow as the roots of a normally land-dwelling species would drown themselves if they stray too far into the water. And lastly, the heavy snow load did the work of bending the leading trunk or branch which became the leading trunk down on the old trunk. This is the power of naturally formed bonsai. A whole life story that spans centuries all told in one pot by the evidence of the trunk and the deadwood and the remaining branches.

|

| Front view |

|

| Rear view |

|

| Back to its perch! |

|

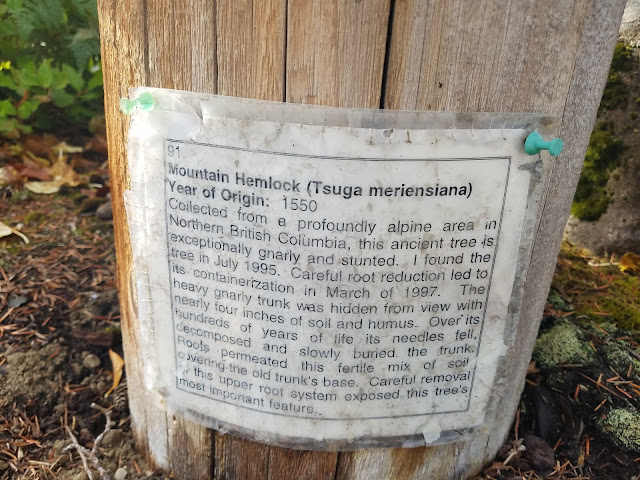

| Dan's sign that accompanies this tree. This tree was counted by counting the rings of a large root cross-section to get the average rate of growth, and extrapolating that age to the diameter of the tree, as I explained in one of my first blog posts. |

As an aside, I am 110% itching to get back to working at the garden again, although I am extra mindful to avoid my older bonsai friends in the midst of our current corona pandemic, lest my mild cough put them at risk. The local Seattle bonsai club has also canceled our events for this concern as well. Luckily, this has given me more time for my own bonsai projects, as well as to go through my archive of past work. If case you find yourself bored in quarantine, or just need more online bonsai resources, consider subscribing to my personal YouTube channel and the Puget Sound Bonsai Association YouTube channel. I am working on putting informative bonsai demonstrations onto both channels - from my work with Dan and from the PSBA's archive of visiting guest artists, respectively. I hope you'll find them to be a helpful extension of my blog!

No comments:

Post a Comment